When you convey what you mean with clarity and impact, you give yourself the best change of being understood and achieving whatever goals you may have.

The skill of explaining our ideas effectively is one of the most highly leveraged. It’s also one of the most neglected.

From presentations at work, to explaining a problem to our doctor, to writing blog posts, being able to communicate with clarify and confidence increases our chance of success.

In his latest book, The Art of Explanation, Ros Atkins has shared the process he uses to write his viral explainer videos and the lessons we can use to improve how we communicate.

The Anatomy of a Good Explanation

But first, what makes a good explanation? How can we know we’ve been successful?

Ros Atkins identifies ten attributes that we should include in every explanation.

- Simplicity. This doesn’t necessarily mean short or less detail. It’s about clarity of language and the removal of distractions and unnecessary information.

- Essential Detail. Every piece of non-essential information makes it harder for the essential information to be communicated.

- Complexity. Actively seeking to understand the complexity of your topic helps you judge which information is essential. It gives you confidence in what you say, even if you don’t use it in your explanation.

- Efficiency. Is this the most succinct way I can say this?

- Precision. Am I saying exactly what I want to communicate?

- Context. Why does this matter to the people I’m addressing?

- No Distractions. This includes not using words or names which might not be known to your audience. It also means avoiding media that isn’t explicitly referenced in the explanation.

- Engaging. Are there moments when attention could waver?

- Useful. If you are answering the questions the audience has, there is a good chance they will want to hear what you have to say.

- Clarify of Purpose. Above all else, what am I trying to explain?

Now that we know what we’re aiming for, let’s look at the seven steps which Ros Atkins suggests we use to get there.

Seven-Step Explanation

Step One: Set-up

Human beings have a long track record of not stopping to ask themselves obvious questions on what they’re about to do.

Before we start thinking about what will be in our explanation, we need to spend 10 minutes figuring out what we’re trying to do. This may seem obvious but explicitly defining this gives us a goal to aim towards. We can’t know if our explanation is successful if we don’t know what we’re trying to communicate.

These questions include:

- What do you hope to explain and/or communicate?

- Who is this explanation for?

- What is their current knowledge on the subject?

- What do they want to learn from you?

- What specific questions for your explanation need to answer?

- Is there a fixed duration?

Don’t move on to the next step until you have specifically answered each question. Better yet, write down the answers and use them as a reference after each step.

Step Two: Find The Information

Once we know what we’re trying to explain, we can start gathering the information that may be relevant.

At this point, we want as much raw information as possible. It’s better to err on the side of too much (we can decide to discard the information later).

Think about what parts of the subject you want to explain and what questions others may have about the subject. Use these as your starting points.

Also keep in mind the questions you still have about the topic. The deeper your understanding of the topic, the more confident and effective you’ll be in your communication.

The goal of this step is to compile as much information as possible in a single place. It’s normal for it to be disorganised, incoherent, and long.

Once we have our raw information, we need to distil it into a form that will make it as easy as possible to organise.

Step Three: Distil The Information

We want each element of information to be in its cleanest and most usable form.

In step three, we need to do two things:

- Refine the information that may be relevant.

- Discard the information we definitely don’t need.

To achieve this, we’re going to perform two sweeps of the information we gathered in step 2.

The First Sweep

Go through each piece of information and ask yourself whether it is relevant to your ‘purpose’ from step 1.

- If it isn’t, move it to the discard pile.

- If it is (or if you’re not sure), keep it.

For each piece of information that you keep, strip out anything that doesn’t have value. The only full sentences remaining should be quotes.

Author's Example

The Second Sweep

After the first sweep, you should have a better feel of what information is available.

This time, you need to be stricter with what information you keep. It must be actively helping you achieve your purpose, or else it will just be a distraction.

Once we’ve finished your second sweep, we should have the core information of our explanation. Now is a good time to check to see if there are any gaps, and return to step 2 if there are.

Step Four: Organise the Information

Now that we have our information, it’s time to organise it into the story we want to tell.

Start by listing out the main sections that you want to cover. At this point the order doesn’t matter.

Then add two more sections:

- Information that you’re not sure how to use.

- High impact information. This will be useful for creating our start/finish.

Once you have your sections listed, think about what order you want to explain them in. A good starting point is to think about how you would explain the topic to a friend.

Re-order your section headings to reflect this order and move the pieces of information from step 3 into the relevant section.

Once your sections are ordered, go through each one and order the pieces of information inside it. If there are any elements left over, move them to the ‘not sure’ section.

Finally, create two new sections: Introduction and End. Move elements from the high-impact section into these sections.

Step Five: Link the Information

Now it’s time to actually write the first draft of the explanation.

Start from the beginning and let the elements you’ve ordered in step 4 guide you.

If you get stuck, try to identify why:

- Are you not sure exactly what you want to say?

- Are you not sure how to express it?

- Are you missing information?

- Do you have too much information?

- Is the order not quite right?

Address any problems you identify. Equally, don’t worry about being perfect - writing something is better than nothing. We can rewrite it later if we need to.

To keep the your listeners engaged, make sure the explanation flows well. Try to avoid hard stops and signal to the user what is coming in the next section.

Once you’ve finished, go through it from top to bottom and check how it feels:

- Do the sections and elements within the sections flow smoothly from each other?

- Are there any gaps in the explanation?

- Are there any sections where you’re struggling to make your point?

For any weaknesses you find, you can either address them now or mark down what needs to be done.

Once our first draft is complete, it’s time to ruthlessly polish it.

Step Six: Tighten

These smaller decisions are just as, if not more, important than dropping a whole section. The smaller edits can give your whole explanation efficiency and momentum.

Now it’s time to delete and refine. It doesn’t matter how long we spent writing it. If a sentence is not as precise and clear as possible, it goes. Go through each sentence and ask:

- Are there any obstacles to understanding?

- Is there unnecessary complication?

- Could any sentence be made shorter without losing their content or meaning (see Common Redundancies in the English Language)?

- Is there anything that is unexplained and could distract?

- Does the start hook you in and the finish leave you with a clear conclusion?

- Has your explanation answered all the questions that people will have about this subject?

- Are all the sections and elements essential? Now that we have a tight explanation, we need to plan how we’re going to deliver it.

Step Seven: Delivery

Read your explanation at a slow-to-medium pace.

Ask yourself:

- Does this sound like me?

- Does each sentence and section logically move on to the next?

Fix any places where it isn’t right.

Finally, annotate your script with notes for yourself. Where will certain visual elements be shown? What would you like to emphasise? Where are the best places to pause for a breath?

Seven-Step Dynamic Explanation

The seven steps described above work well for situations where we have full control over what we say and the order in which we say it.

However, there are cases where we need to give explanations where we need to be more flexible. For example, we may be answering questions in an interview or a meeting. Ros Atkins calls these dynamic explanations.

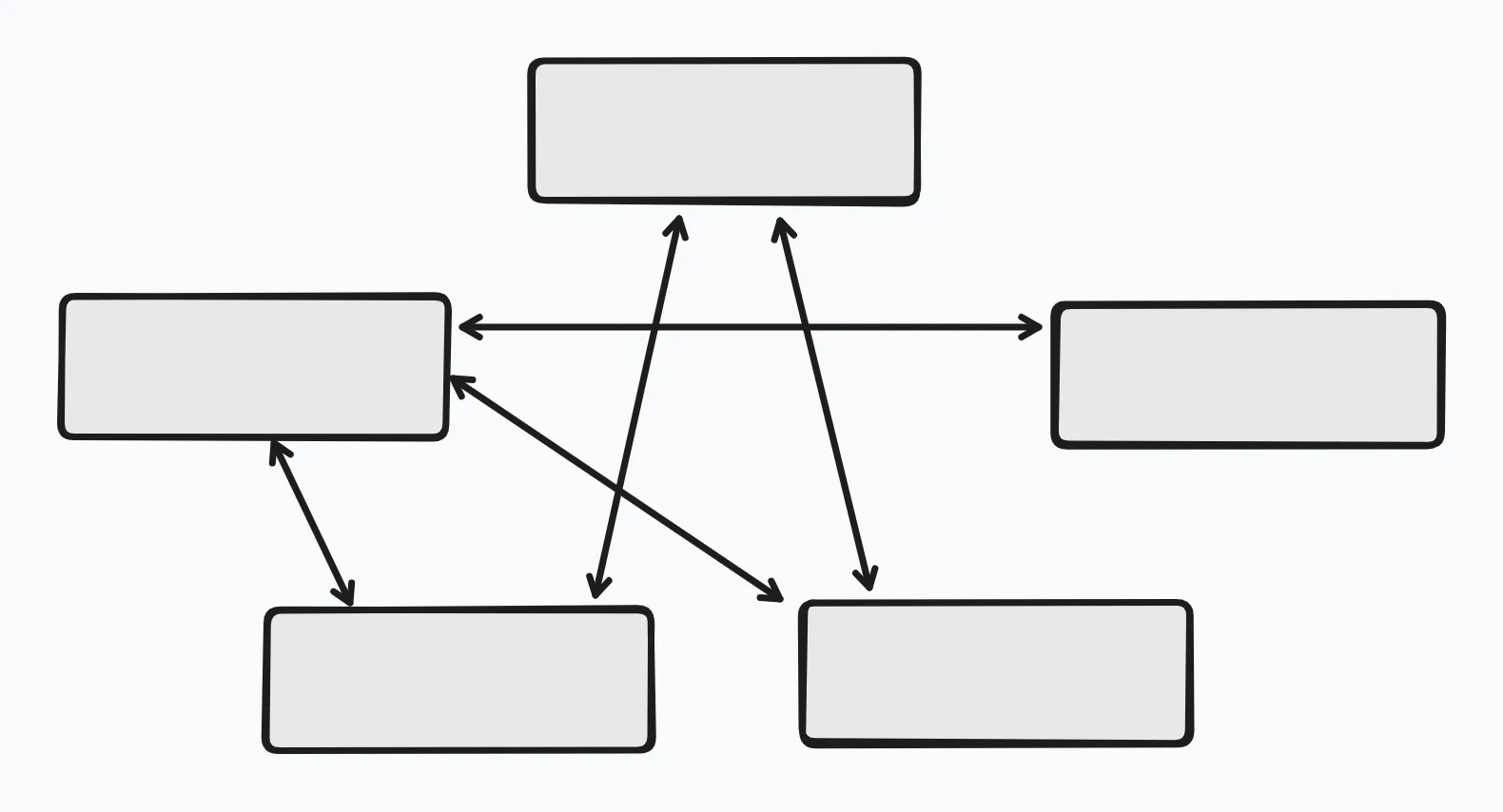

When we are preparing for dynamic explanations, the first 3 steps are the same as before. After we have distilled the pieces of information though, we need to organise it in a way that allows us to be flexible.

Step Four: Organise the Information

Step four for dynamic explanations is very similar to step 4 for normal explanations. However, now we’re going to be thinking on our feet. So our building blocks need to be simple, memorable, and usable.

- We’ll limit ourselves to no more than five pieces of information per section.

- If you have a lot of sections, you may want to group together sections which connect closely together

Step Five: Verbalise

If the first time you try to construct verbal explanations is when you’re doing it for real, the chances of it going well are really quite low in my experience.

At this step, we’re going to practice verbalising the different sections and how they connect together.

Start by talking through individual sections. Allow yourself to look at the information and try to verbalise each strand. Make sure what you’re saying supports the ‘primary point’ that you’ve chosen for each strand.

Next, pick any two sections and talk through one and into the other. Try out different ways of transitioning between the sections.

Repeat these steps until you’ve practiced talking through each sections and transitioning to others. The more combinations you practice, the more flexible you’ll be able to be.

Step Six: Memorise

We likely won’t have access to our notes during the explanation so now we need to memorise the notes we made in [[#Step Five Verbalise|step 5]].

- Start by just reciting the pieces of information from a section.

- Then try to explain a whole section without notes.

- Once you’re happy with individual sections, move on to reciting two or more sections. Try the sections in reverse order.

Finally, write the section headers on pieces of paper and pull out random ones. See if you can explain those sections in that order from memory.

Ideally, the whole isn’t just to make it manageable. We want to get to a point where explaining the sections and organising them becomes automatic.

Step Seven: Questions

Dynamic explanations are most likely the result of being asked a question. So for the final step, we need to look at how we’re going to adapt our explanations to provide an answer that is relevant, efficient, and clear.

Create a list of questions you may be asked. Focus especially on questions you would feed uncomfortable being asked.

Split the list into three:

- Questions you think you can answer. For each of these questions, think about which combination of sections would answer the question and practice them. Make sure you feel confident delivering it.

- Questions you need to work on how to answer. It’s important not to ignore the feeling of discomfort these questions give you. Try to figure out exactly why you don’t feel confident and then address the problem.

- Questions you need new information to answer. We can’t prepare detailed answers to every possible question. But we should try to anticipate what questions we may be asked and make sure we have at least something to say in response.

One danger we may find is that we end up giving rote responses that don’t directly answer the question. One way to avoid this is by using mirroring language. We can use the language of the question in our response. For example, if we’re asked about how we’ve shown good “judgment” in the past, we can make sure to include the word judgment in our response.

Quick Explanations

In our day-to-day lives, most of the explanations we give are quick and short. Emails are a perfect example of this.

Unfortunately, the recipient of our email is unlikely to find it as important as we do when we send it. So to maximise the chance of us being able to communicate what we want effectively, we need to approach the email with 5 assumptions:

- The recipient/s may not read it at all.

- The recipient/s may not read all of it.

- The recipient/s will skim it rather than going through it sentence by sentence.

- The recipient’s approach will be entirely functional.

- If the recipient doesn’t feel that it’s specifically for them, they are far less likely to read it.

To counteract these assumptions, we need to make it as easy as possible for the reader to understand why they’re receiving the email and what our message is.

- Explain the message in the first sentence. For example, “Hi Joe. I’ve four questions I’m hoping you can help me with.”

- Make your message as short as possible.

- Formatted the email to be skimmable.

- Make it as easy as possible to respond to. For example, “Here are three numbered options, please reply with the number that you choose.”

- Make sure you answer the reader’s questions.